I Am American

“Where are you from originally?” I’ve lived with that insidious question my whole life. Most. . . no, ALL of us ethnically ambiguous sorts have lived with this question our whole lives. And when I watched Kellyanne Conway ask reporter Andrew Fienberg “What’s Your Ethnicity?” the hairs on my neck stood up and my breath caught in my throat.

I know that question all too well. And I know how it highlights the otherness of the person being questioned. I know how it makes me feel like the questioner thinks my olive skin, slant eyes, and other ethnically ambiguous features don’t quite belong in this country. At a social gathering, the conversation starts out innocently enough. Someone asks, “So, where are you from?”

“I’m from Colorado,” I reply.

Sometimes I imagine the follow-up question is about something stereotypically Coloradoan like skiing or mountains. Instead, it’s, “No, I mean, what nationality are you?”

“Uh, I am American.” An unnecessary clarification because Colorado is, in fact, a state.

With a sigh, they add, “I mean, what’s your ethnicity?” The question is usually drawn out dramatically in a way that implies the round-faced, high-cheekboned, olive-skinned, flat-nosed, slightly-slanted-eyed women standing in front of them might be a bit daft. They apparently mix up “look of annoyance” with “look of stupidity” as easily as they mix up “nationality” with “ethnicity.”

Newsflash, ethnicity and nationality are different.

Instead of retorting with something clever like “I am human, what are you?” I cut to the chase and reveal my parental pedigree. The response is usually to just dive deeper into my mixed ethnicity. Although the person feels they are being complimentary, the comments veer into pointing out each of my “interesting features” features that make up my “exotic look.” It feels like they are taking a general an inventory of my otherness, my ethnically ambiguous self. Soon, they offer a suggestion, “Ever plan to visit your homeland?”

Do I plan to go back to where I came from?

I roll my eyes, squint at the person (which probably makes them look more slanty) and I deadpan, “Sure, I go back to Colorado every few years.”

Undeterred, with the same slow “you don’t understand” drama, they reply, “No, I mean the Philippines.”

“Why would I do that? A brutal dictator is running the place and he murdering Filipino citizens!“

The fact is like Ayanna Pressley, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Rashida Tlaib, my homeland is the United States. And like Ilhan Omar, the country I align myself with is the United States. I am standing in my homeland.

I am American, through and through.

I was born to two American citizens. Although half of my DNA came from a man born in the Philippines, I have no connection to the country. I hear about the Filipino president on NPR, but honestly, I don’t think I easily locate the country on a map. My father left the Philippines at the age of five, more than 70 years ago. He arrived in the ports of Hawaii before the islands became our 50th state.

Hawaii became a state 1959 and my dad became a naturalized US citizen. He and his brothers all chose to serve their homeland (the United States for those of you not getting the drift) during the Vietnam war. The story my father has told me about his homeland is that as a young GI preparing for deployment to Vietnam, he returned to the Philippines. Unfortunately, his motherland did not warmly welcome him home, and he vowed never to return.

My mother is at least a fifth-generation American. In the late 1800s, my great-grandparents immigrated to Kansas, the original motherland of Great Plains Indians like the Arapahoe, Cheyenne, Kiowa, and Comanche. My great-grandparents settled there after emigrating from the eastern US. Their emigration was preceded generations before by emigrants from England and what is now Poland.

No one ever asks when I plan to visit England or Poland.

My parents met when my mother took summer classes at the University of Hawaii. That summer school trip wasn’t nearly as bourgeois as it sounds. Sure it was paradise, but she supported herself wearing elbow-length rubber gloves to protect her from pineapple acid on the canning line at the Dole factory. Tired from work and school, she fell asleep waiting for a bus where my father met her. In 1968, they married. For the occasion and to the delight of the town’s only florist, a Hawaiian Auntie shipped boxes of tropical flowers to my mother’s 1200-person Kansas hometown.

They each had full-time jobs, paid their bills, and soon they had a baby on the way. Before they moved to Colorado, my brother was born in Oklahoma which makes him not exotic, but an “Okie.” They were like any other young couple in the Midwest. Except they faced racist and bigoted obstacles like landlords rejecting them because they were concerned my father might engage in uncivilized Hawaiian rituals. His otherness and the weirdness of their inter-racial marriage is sufficient reason to say “no.”

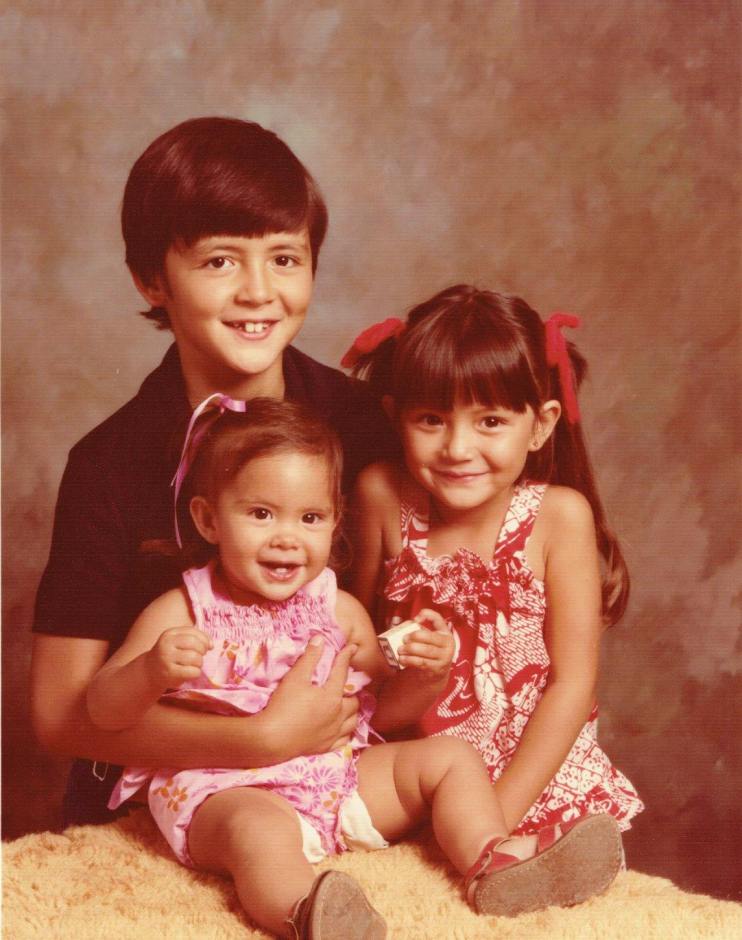

I was born in 1975, the same year the Vietnam war ended. And my sister came along four years later. People often asked my mother, a striking, blond-haired, green-eyed Midwesterner, if she had adopted Vietnamese orphans. Her heart broke a little bit each time someone asked if the brown, slant-eyed children that came from her own womb weren’t her own.

People would ask to hold these strange, little exotic creatures. I screamed and cried at strangers touching me. Even then, people highlighting my otherness exasperated my senses. Perhaps these touchers thought of mixed-race,

ethnically ambiguous kids and babies like little toys from a faraway land. Sorry, we are “Made in America.” Nothing “exotic” at all.

I grew up at the bottom of the broad middle class. We lived hand-to-mouth barely covering our debts. My parents mortgaged the lifestyle to its eyeballs, but we had a house, a dog, two cars, three kids and loads of stuff. I figure one thing that contributed to my father’s outward anger was that, despite his flagrant embrace of all its trappings, America doubted his Americanism.

I attended public schools in a neighborhood with a mix of gang-bangers and delinquents, middle-class kids who were called “rich,” and a mix of race and ethnicities. There were a few close friends, but I mostly floated between social groups. I might one day hang out with a group of black-clad smokers, the next day with the newspaper and yearbook writers and the next with the popular crowd. Perhaps this was all because I didn’t have a strong sense of ethnic identity.

I didn’t feel white. I also didn’t feel Asian. I just felt like a kid trying to get through my teens.

When I graduated near the top of my class, I went to a Colorado State University. I worked two part-time jobs and took a full load of engineering classes. I applied for every scholarship I could. I received several rejections, but I also won awards ranging from $50 to $1000. I had to fill the gaps with student loans which required a lengthy appeal for independence every year because of child abuse circumstances that I won’t get into here. I graduated cum laude then attended MIT on a prestigious, merit-based National Science Foundation Fellowship.

One of my white, male classmates said “Well, you are lucky you are a minority and a woman. You get those scholarships.” None of my scholarships had an ethnic or gender requirement. This guy had never applied for a single scholarship and his GPA was a full point and a half below mine. Let me spell this out for you – he thought I took something he was entitled to because I was minority, ethnically ambiguous, and female and not because I was better than him in academics, community service, leadership roles, and hard work.

I embody the American Dream.

I obtained the ever-so-elusive social mobility to live a better life than my parents. So, why is my Americanism in doubt? Or as Andrew Fienberg asked, “Why is that [my ethnicity] relevant?”

As the exchange between Fienberg and Conway progressed, my anger grew when Conway used her white, European ancestry to emphasize her point. Perhaps she was planning to condescend her way toward the idea that the president might tell her to go back to Italy or Ireland. To be certain, Conway’s intent behind this question, in this setting, amid this political atmosphere, at this moment in history was insidious and ugly. I acknowledge, most people who have asked me “What is your ethnicity?” were not, like Conway, intentionally wielding the question as a political tool to reinforce structural racism, but they are playing into the same systems and power structures that Conway did.

Leave a Reply